The story of Humboldt: Google's sea monster

Humboldt is Google's new subsea internet cable. Find out what it could mean for the Asia-Pacific region.

In 2021, highspeedinternet.com surveyed 1,000 Americans. The goal: to find out if non-experts could explain how the internet works.

Among other things, the survey revealed that 60% of respondents thought "the internet" and "the World Wide Web" were synonymous.

In fact, the World Wide Web is the platform we use to access websites. The internet, by contrast, is a physical network of routers, modems and devices – and cables.

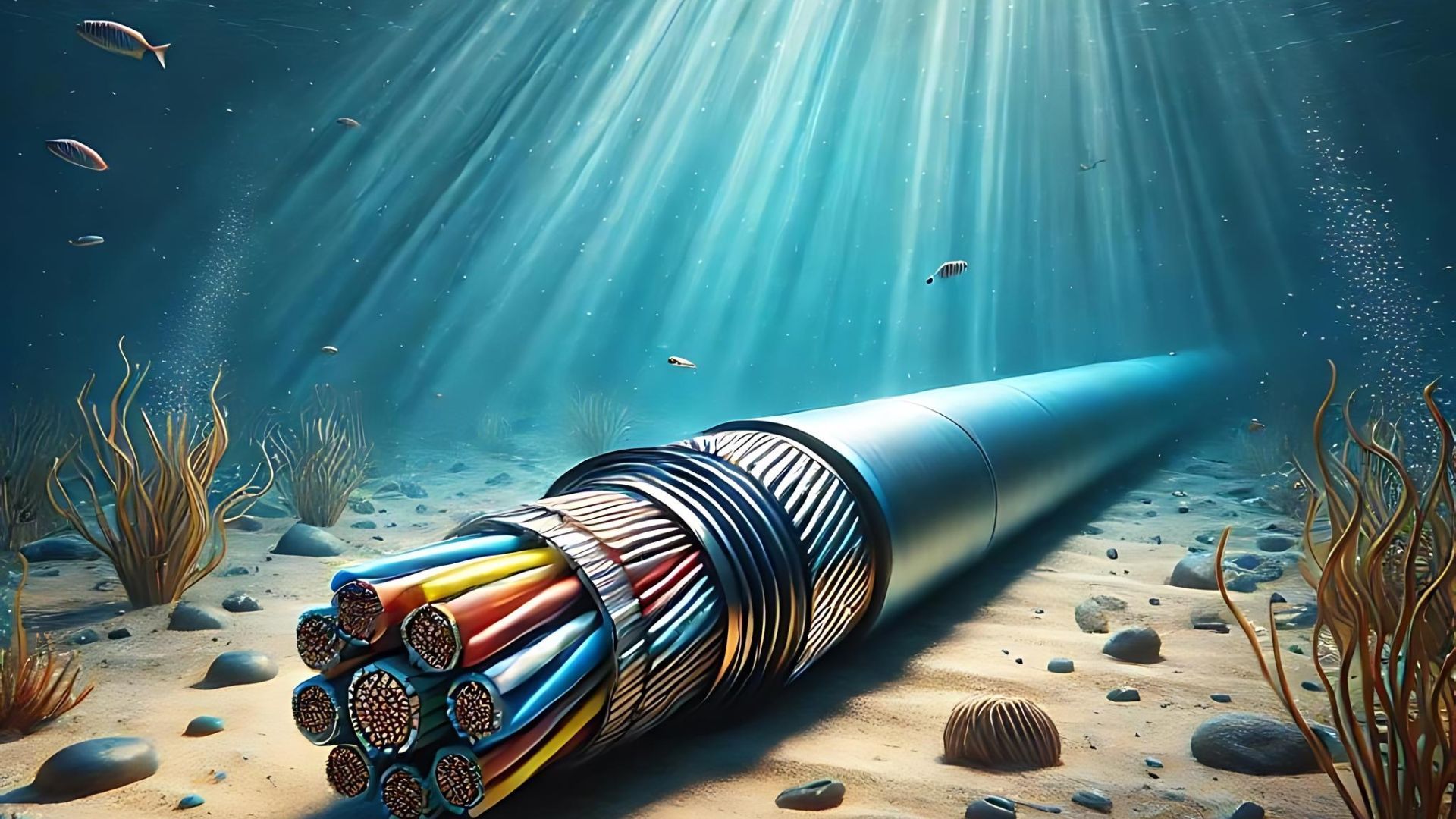

It would be interesting to redo the survey and ask people if they knew where those cables were. We suspect many would be unaware that miles and miles of internet cables are laid directly onto the seabed – around 750,000 miles if you laid them end to end.

These copper-cased bundles of super-fine wires transmit packets of data day after day. They've been

called "the backbone of the internet, carrying 99% of the world's data traffic". Without them, the world's economy would grind to a halt.

It's no surprise, then, that as demand for the internet – and the cloud in particular – grows, so too does the demand for these underwater transmitters, the clipper ships of the digital age.

Look at a

map of the network and you'll see how these cables are distributed. Thick bunches of cables connect Western Europe to the USA and the USA to China, with thinner strips keeping Australia, India and other Southeast Asian countries connected.

You'll notice, too, that some areas of the world are thinly represented – Africa, for instance, is

visibly underserved compared to the global north. But there's also nothing connecting South America to Asia-Pacific.

That, however, is about to change.

What is Humboldt?

Humboldt is a proposed subsea cable that will directly connect South America and Asia-Pacific for the first time.

This is building on two things: Google's previous investment in Latin American digital infrastructure and Chile's ambitions to improve its connectivity.

Google's previous investments in the region have included the Firmina subsea cable, connecting Argentina to North America, with stop-off points in Uruguay and Brazil.

What could this mean for the region? According to Google, it will "strengthen the reliability and resilience of digital connectivity across the Pacific by interconnecting the cables that comprise the South Pacific Connect initiative and adding geographically diverse cable investments that link Polynesia and Chile".

Meanwhile, global tech consultants Analysys Mason have estimated this investment will create somewhere in the region of 740,000 jobs by 2027.

At the very least, it will mean the Asia-Pacific region in general, and Chile in particular, will have better access to tools that are taken for granted in the global north – Google solutions such as Search, Gmail, YouTube and Google Cloud.

Why is it called Humboldt?

Google likes to name its subsea cables after notable scientists. The Curie cable, for instance, is named after Marie Curie: the first female Nobel Prize winner whose work on radioactivity shaped 20th-century science.

Humboldt is named after the German polymath and geographer Alexander von Humboldt. We don't have room to do justice to his achievements, but perhaps most relevant to Google's work in the Asia-Pacific region are his travels to the Americas at the turn of the 19th century.

His scientific perspective on this part of the world led the South American independence leader Simón Bolívar to say this: "The real discoverer of South America was Humboldt, since his work was more useful for our people than the work of all conquerors".

The name was chosen by Chilean residents via an online poll.

What's next for Google's subsea cables?

Humboldt isn't Google's only proposed investment in the Asia-Pacific region. It's also announced that it will invest one billion US dollars in two subsea cables joining the USA, Japan and various island territories in the Pacific.

As so often in the world of big tech, there's a geopolitical element here. China and the USA are vying for influence in this part of the world – and digital investment is all part of the competition.

How do Google's subsea cables fit in with their global fibre network?

Subsea cables are essential to the running of the digital economy. But they are to the internet what cables are to the electricity grid, acting as bridges between generators. In the case of the internet, these generators are data centres.

Google's global network is built around data centres. Individual machines are connected with fibre. These are connected to other facilities nearby. These, in turn, are joined to other parts of the world with long-haul cables, some spanning entire mountain ranges. Subsea cables are there to continue these connections across the oceans.

Google chooses where cables are needed by predicting capacity over five-year periods. This is a tricky task that requires a lot of data from a lot of sources.

It's not just hard at work on improving the capacity of Google Cloud worldwide, however. It also invests significant time, money and talent in increasing fibre capacity.

This is partly done by replicating subsea cables in the lab, daisy-chaining fibre optic spools that would stretch for 80 kilometres when unwound.

These are then analysed in a quest to create more efficient fibre cables. The challenge is finding out how to fit more hair-thin fibres into cables that will stretch from continent to continent.

What's next?

The subsea world has always been a place of human endeavour – from submarines to deep-sea divers to the first telegram cables. It's no wonder that it's now the backbone of the digital world, powering everything from large enterprises to local start-ups.

At Ascend, we follow tech news closely. Watch this space for updates about Humboldt, subsea cables and the cloud in all its multifaceted, multinational glory.

Based in Cork, Ireland, Ascend provides bleeding-edge

cloud transformation solutions and consultancy. We're here to accelerate your ambition and take your digital transformation to the next level. Don't hesitate to

get in touch for a free, no-obligation consultation.